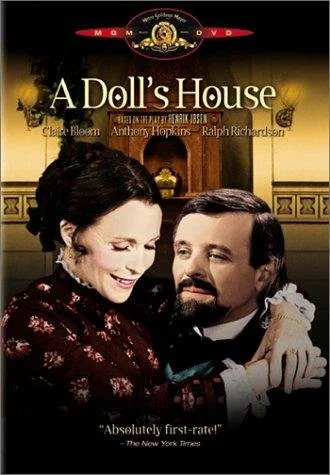

A Doll House: Is Nora Good with Money?

One of the best questions to ask when students have read Act 1 of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House is simply, “Is Nora good with money?”

This question allows the class to discuss Nora’s character, money and debt (a major topic of the play) and, not-to-be-overlooked, the plot of the play.

So is Nora good with money?

Well . . .

Yes. While it is true she forges her father’s signature in order to secure a loan of enough money to take her sick husband Torvald to Italy in order to save his life, she gets away with this crime for eight years. She pays for a health-vacation and saves her husband’s life. (Torvald believes that Nora received money from her father when he died to pay for the trip).

So Nora has a secret debt for which she has to pay a monthly loan payment with no income—other than what Torvald gives her as an allowance. Nora takes the money Torvald gives her and somehow manages to feed the household and dress the children—and herself!—minus her monthly loan payment to Nils Krogstad. That’s pretty impressive.

Nora seems to be a bit impressed with herself as well, telling her friend Kristine that she never skimps on the children, but buys herself cheap dresses (and it’s a good thing, she says, that everything looks good on her!)

Sometimes, even, Nora takes on extra jobs to help pay her secret monthly loan—such as the time she took on some copying work at Christmas (and pretended to be making decorations for the tree that that darn cat tore up at the last minute).

It’s not easy for Nora, though. She’s always desperately chasing after money to make sure she has enough—both for the household and for her debt. She’s constantly wheedling Torvald for more money, which is why he calls her a “spendthrift.” He thinks he gives Nora plenty of money to maintain the house, so the only explanation for why she’s always needing more is her bad budgeting ways.

So it seems that Nora is good with money. And yet . . .

No, Nora is not good with money.

The first thing we see her do in the play (besides sneak contraband macaroons) is overtip the boy bringing in the Christmas tree. Then, when proudly telling Kristine Linde of how she’s been secretly paying off a loan every month for the past eight years, Nora reveals that she doesn’t understand something called “amortization”

But what do you expect? Nora lives the life of a child receiving an allowance from her father—er, husband. Why should she understand the world of business or law (or religion) since she’s always either taken care of by a male authority figure (father or husband) and never allowed into those worlds?

Simply asking “Is Nora good with money?” allows the class to dig deeper into the plot of the play (“What’s at stake?”) and into Nora’s character (which is clearly intelligent—even clever—and yet infantilized due to her social role as wife).

One good question (and they are hard to find) can crack open a great work beautifully.