Kafka: Gregor and the Elephant Man

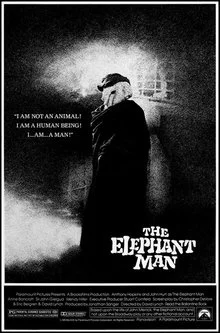

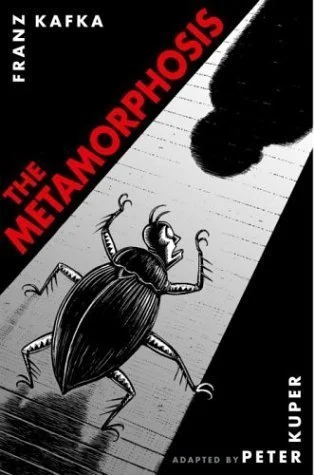

As I read and discussed Part 3 of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis with my students—in particular, discussed Gregor’s death scene—I could not help but remember the death scene of “the Elephant Man,” John Merrick in David Lynch’s 1980 film of the same name.

I had first seen that film my freshmen year in college in one of the greatest classes I’ve ever taken: Humanities (Empire in Crisis). I remembered the film had affected me deeply with its stark black and white colors, the industrial noises, the carnival barker’s patter intro for John Merrick, the running-through-the-train-station scene and the “I am not an animal!” speech, and—of course, how Lynch depicted Merrick’s death.

I decided that after we’d finished our discussion of Kafka’s novella that we’d all watch the film and do a little comparing and contrasting.

Gregor and John (“The Elephant Man” was named Joseph in real life, but Lynch changes his name to John for his film) do have a lot of commonalities. Both are hideous to look upon. Neither of them chose to be hideous. Both are trapped in the cages of their own bodies and have to endure that existence. Both have inexpressive faces that cannot be read. Both have beautiful, generous, sensitive souls. Both characters have profound experiences with art, and both have deeply affecting—though quite different—death scenes.

What I learned most by comparing these two works is that The Elephant Man (which is a horrific and wonderful work of art on its own) helps me appreciate the genius and horror of Kafka even more.

Whereas Merrick has access to language and can communicate his humanity to others, Gregor does not. Whereas Merrick has a deformed, enlarged head and repulsive body, he is still human-shaped, Gregor is another species from the human entirely (and not even mammalian or human-like at all). Whereas Merrick makes friends of his doctor, Treves and others of the hospital staff and is often treated kindly, Gregor is alienated from everyone and only briefly knows his sister Grete’s kindness in Part 2. Kafka’s dark genius, though, is to make even Grete’s kindness oppressive to Gregor since he cannot communicate her gratitude to her. Whereas Merrick travels across London to different locations, Gregor barely leaves his bedroom before being forced to return to it again and again. While both Gregor and Merrick suffer immensely, there’s little question that Gregor suffers more in so many different ways.

Lynch’s story of John ends with Merrick escaping his abusive “owner” Mr. Bytes through the help of other friendly, carnival “freaks” and returning to the safety and love of Treves and the hospital staff. Merrick dresses in a tuxedo and goes to the theatre to see a show that enraptures him and where he is honored by Mrs. Kendal and the whole audience with a standing ovation.

Merrick returns to his permanent room at the hospital after this marvelous night and works on his model cathedral of St. Phillips. He completes the model and signs his name to it, sighing, “It is finished.” As he lays down his pen, the first notes of Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” begins playing.

Lynch had carefully shown viewers earlier in the film that Merrick—because of his enlarged head—is unable to sleep like “normal” human beings. In several scenes, we see Merrick “sleeping” in a painfully crouched position with his head on his knees. If Merrick lies down, he will die.

In Merrick’s room are two sketches of children sleeping, tucked into their cozy beds. After Merrick has signed his cathedral model, he turns to look at the pictures. He gets up slowly and moves toward his bed, stacked high with pillows to keep his form upright, and slowly moves every single pillow off the bed.

As I watched the film with my students, I remembered how this scene hit me almost thirty years ago, and I felt it “hit” some of my students as well. I could feel their realization (echoing mine): “Oh! Oh. He wants to sleep like the children in the pictures. He wants to rest and be like everyone else. Oh no. He can’t! If he lays down ‘normally,’ he will die. Oh no. He is okay with dying. He wants to go out peacefully after a night of such wonder and acceptance.” Barber’s strings swell as Merrick lies down to rest at last. It is deeply moving.

Gregor’s death is both similar and different to Merrick’s, depending on how the story is being illustrated and on how we want to interpret it.

Merrick’s death has dignity and meaning, mostly because it was chosen by him. Lynch depicts Merrick as a martyr (echoing Jesus’ final words), ennobles his choice with Barber’s music and with Merrick’s slow, intentional, methodical removal of the pillows.

Gregor’s death’s only dignity is in his retreating to his room (like a dog or cat that retreats or hides in its death and wants to be unseen). Gregor’s dragging of his body by forcing his head against the floor feels like the Stations of the Cross in the Passion of Christ—although Kafka only links Gregor to Jesus in that the events of the novella occur from Christmas to Easter. Gregor—if he alludes to Christ at all—is a parody of Christ, not an actual Christ figure—even if one of my favorite illustrations of the story explicitly places Gregor’s dying body in a cruciform pose.

Most crucially different though is that while Merrick chooses his death, Gregor’s head “falls of its own accord” or “without his consent” or “against his will.” Gregor’s bug body kills him, rather than Gregor choosing to die.

Lynch’s movie ends with images of Merrick’s mother’s tender face (“the face of an angel”) and a lovely recitation of Tennyson’s “Nothing Ever Dies”—but Gregor’s body is literally thrown out with the trash by the callous and frightening charwoman. No funeral, no burial, no memorial. In fact, in darkly comic fashion, a happy ending is provided: the wrong to the family has been set right, and Grete—at home in her body in a way Gregor never was—stretches in the sun to her parents’ delight.

It’s hard to say what the death of “the Elephant Man” means, but it undoubtedly means something about human dignity. Gregor’s death may mean something outside of the novel, but inside the story, it has no meaning or significance at all. Gregor’s suffering is as meaningless as his death.

Lynch’s movie is hard to watch. The film doesn’t really have narrative drive (“slow and sentimental” are the usual criticisms of the movie) and it is unlike any movies that students now experience (if they have the patience to watch any movies at all)—but, I think—based on student comments—that most of them found it very powerful and different enough to be worth their time.

For me, comparing and contrasting the novel and film gave me a greater appreciation of both—especially of “appreciating” the even deeper horrors of Gregor’s experience. What I’ve learned is that part of Kafka’s genius is that he had the gift—maybe greater than typical horror writers like Poe, King, or Lovecraft—of writing about unfathomable horrors and terrors that only deepen the more you contemplate them. In the guise of a “flat” style and fairy tale logic, he presents the grimmest and darkest picture of existence ever written. No contest.

(And tip of the hat).