love the human

On the first day of school, I now have a standard activity that prevents me from just droning on about my syllabus and gets students up-and-moving and involved in playing with language (which is what, to my mind, the English classroom is all about).

I learned this activity from the amazing teacher, Miranda Smith—and I think she learned it from Susan Barber: the sentence strip construction activity.

Basically, all the activity entails is cutting up a poem into its separate lines, placing them in a bag (like a puzzle)—and then asking groups of students to put them together in the “right” order (or an order that best makes sense to them).

Great poems that other teachers use are Maggie Smith’s “Good Bones” and Ruth Moose’s “The Crossing.”

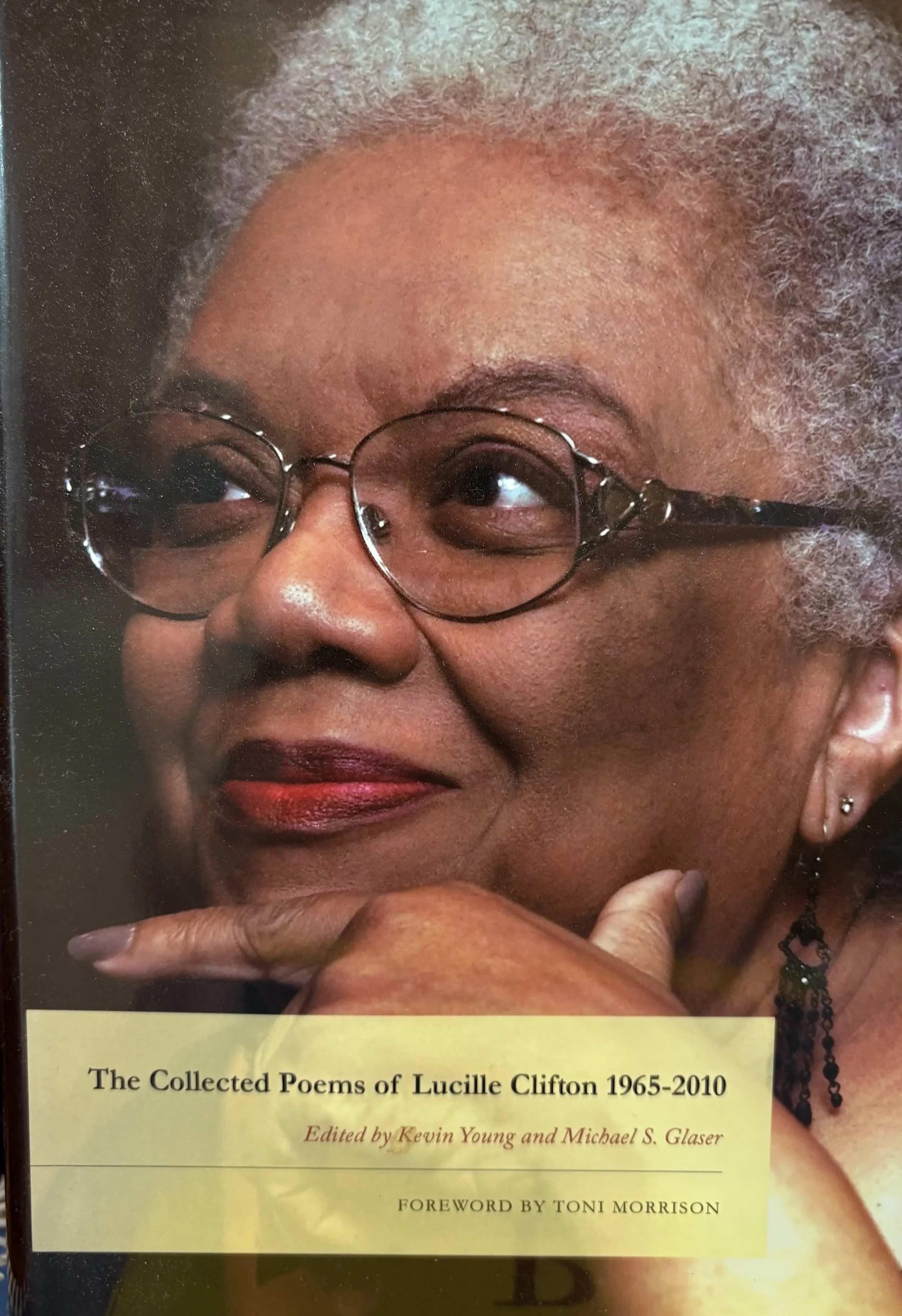

I like to use a poem by one of my many classroom Patron Saints: Lucille Clifton.

Specifically, I like to use Clifton’s poem “love the human” for two reasons:

1. The poem is free verse and without punctuation (though a few interesting “spacings”) so students can’t just use rhyme scheme to “solve the puzzle.”

2. The poem introduces students to the year-long theme of my class.

The poem, “love the human,” is what I call a “command” poem. Its lines are a list of commands—some abstract and some specific and granular—to love the human, starting with the epigraph from Gary Snyder that begins the poem.

The poem emphasizes what makes us human: our physical bodies in all their frailty and “grossness” and our cultural habits (gathering in small groups together in sorrow or joy, making noise or being silent).

At the end of the poem, Clifton commands us to love “even the improbable foot even / the surprised and ungrateful eye.”

After the student groups have assembled their poems, they walk around and compare their “answer” to other groups, and we talk about the construction and meaning of the poem.

I tell them that Clifton’s command—to love the human—is going to be our focus for the year. For every work of literature we read, we are going to ask, “How well did the author love the human?” I tell them that we are going to meditate—all year long—on what being human means. What is a human being?

When the year is over—and after many discussions over “loving the human” in class—I ask students to write a paragraph in their End-of-the-Year Portfolio to describe what “loving the human” means to them.

The phrase, like so many phrases in great poetry, multiplies and deepens in meaning over the course of our study. What the phrase means to me might be slightly different than what it means to my students.

And the command to “love the human” ultimately is difficult for us all at times, but that’s precisely why I think the phrase is the talisman that holds all my class, curriculum, and thoughts together.